Review: Bennetta Jules-Rosette and J. R. Osborn, ‘African Art Reframed: Reflections and Dialogues on Museum Cultures’

African Art and the Transformational Role of Museums

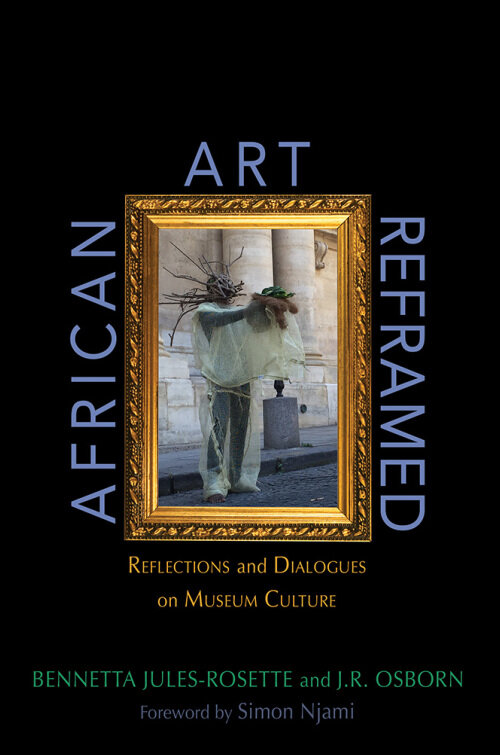

Review of Bennetta Jules-Rosette and J. R. Osborn’s African Art Reframed: Reflections and Dialogues on Museum Cultures (University of Illinois Press, 2020), 408 pages. Foreword by Simon Njami.

Abstract

There was a time when Africa was thought to have no history, no philosophy, no civilizational sensibilities and indeed no artistic creativity. If Africa had any art to speak of, it is at best primitive art that lacks sophistication both in conception and execution. This new book, African Art Reframed: Reflections and Dialogues on Museum Cultures by Bennetta Jules-Rosette and J. R. Osborn re-evaluates this perception and argues that African art has come a long way in the last few decades. It takes the reader through the transformational process that African art has undergone in that period, including the role of the museums and the collaborative work of agents across different sectors in reframing of African art.

Reviewed by Gabriel O. Apata

In 1897 a British colonial expeditionary force led by one James Roberts Phillips was making its way to Benin City in what is now Nigeria, ostensibly to discuss a treaty dispute with the Benin King Ovonramwen. Unbeknown to Philips and his men word had reached the palace that Philips’ mission was not for peace but war and so a local army was speedily assembled, which ambushed Phillips’ convoy, killing all but two members of the expedition. What happened next was one of the greatest acts of pillage and destruction that the British colonial machine ever visited on Africa. Because in response, a ‘Punitive Expedition’ under the command of Admiral Harry Rawson set sail for Benin and on arrival seized the king, torched the palace, raped and massacred hundreds of the local population, destroyed historic monuments and structures, effectively laying waste to one of Africa’s ancient civilisations. Phillips’ intention had been to gain control of the Kingdom’s precious commodities like palm oil and ivory, but Rawson and his men discovered, perhaps to their surprise, thousands of arts and crafts, which they looted and carted off to Europe. The irony is that the looting of Benin artworks occurred at a time when Africa was thought to lack civilizational creativity and aesthetic sensibilities, which begs the question: what value did Rawson and his men see in these objects? Did they see them as mere commodities like palm oil or ivory, or as curiosities that might interest others; or did they see them as precious artworks worth protecting and preserving? We may never know the precise answers to these questions, but what we do know is that these objects were taken as spoils of war, some of which the men kept as mementos, while the rest were sold off to recoup the cost of the expedition. Which is how many of them ended up in Western museums. African art has come a long way since 1897 and has undergone a remarkable renaissance in the last few decades. But how exactly has African art been transformed?

The answer to this question forms the basis of African Art Reframed: Reflections and Dialogues on Museum Cultures, by Bennetta Jules-Rosette and J. R. Osborn. At just under 400 pages, this splendid and impressively researched book has eight chapters that divide thematically into three parts, with a compliment of pictures: artworks, artists, museum exhibits and others, while interviews with artists and curators close each chapter. This is the story of African art told principally from the perspective of the artists that create them, the museums that keep and exhibit them, the curators that curate them, and the public that goes to see them.

The authors identify five transformational phases of African art, which they describe as ‘transformation nodes’. ‘A nodal transformation’, they explain, ‘occurs when the museum as a social institution shifts its structure and audience’ (13) and these nodal phases are: (1) ‘cabinet of curiosities and the modern private collection’; (2) ‘the small gallery space’; (3) ‘the modernist representational museum with imposing edifice’; (4) ‘the postmodernist interactive museum’; (5), ‘virtual museum without an edifice’ (p.7).

The first phase relates to the objects in private collection, which nobody gets to see. Avid collectors of ‘primitive art’, like Augustus Pitt Rivers and Charles Ratton, both mentioned in the book, had to bequeath their collections to museums, perhaps for this reason. The transfer from private to public space (starting with small galleries) begins the reframing process; but the museum is where the significant transformational shift (nodes 3-5) occurs. ‘Museums’, they write, ‘are ultimately the arbiters of what they classify as African art from the inside’ (186). In another passage they stress the same point, writing that:

we contend that African art is framed by the modalities of museum presentation, which provide a social context for the curatorial narratives and the artwork. It is this nodal transformation, involving curators and artists collectively, that reframes African art and releases it to the public. The process of reframing African art totalizes the process of displaying, exhibiting, unmixing, and remixing the art for diverse audiences, thereby bringing our methodology to a solid conclusion. (274).

The reframing or transformational process involves a combination of contributory efforts of the many stakeholders, including the market, because the ‘market involves the intervention of cultural brokers, collectors, curators, critics, and publishers. Researchers also play a crucial role as cultural brokers. By providing historical, anthropological, and aesthetic commentaries on artworks, they contribute to the diffusion and appreciation of the pieces’ (186). This idea is similar to Becker’s argument in Artworlds (1982) where he argues that art is ultimately a ‘collective activity’. Aesthetic value here consists in the interplay of factors that take place within the public space, resulting in what Hume in On the Standard of Taste (1757[2018]) calls ‘joint verdict’, that moves from the individuality of the aesthetic judgement to a public debate and consensus. Art and the idea of taste are therefore socially situated, giving rise to a multiplicity of ‘social meanings’ or the sociology of art as we find in Bourdieu (1984), Janet Wolff (1983, 1984), Vera Zolberg (1990) and others.

Thus, the museum is central to the collective and socialising process of art. Indeed two of Foucault’s heterotopic spaces are the museum and the cemetery, both places of death, of memory, memorials, mourning, reflection and remembrance. But unlike the cemetery, museums are places of resurrection, restoration, rebirth and celebration where the dead past is brought back to life and inspirational ideas derived. They are also educational spaces of learning that shape people’s views of the past and which helps them to reimagine the future. Museum visitors create new aesthetic ontologies and epistemologies through their interactive, interpretive and public discussions on art. But the museum itself as a work of architectural art much like the objects it exhibits, which enhances further the aesthetic experience. However, in the absence of physical access to museum, modern technology has provided another dimension to the experience through interactive engagement, complementing the nodal transformatory process.

That is not all. Museums function as religious establishments or sacred places, a temple for instance, where certain rituals are observed. These secular cathedrals of aesthetic and cultural worship are spaces of spiritual encounters where people come to find meaning through their encounter with the objects on display. Drawing on Goffman, the authors explain how the backroom/frontroom process works with regards to collection, where backrooms are no mere storage spaces but preparatory staging post for eventual exhibition. Certain African artworks in particular are perceived as redolent of totemic meanings that outsiders may not be able to understand at first glance. Yet, this absence of immediate penetrative interpretative understanding adds a kind of Benjamin’s ‘aura’ that forms part of its appeal. In addition, museum visitors are like tourists who visit ancient sites in search of meanings those places might hold, as MacCannell’s The Tourist (1976) argues. MacCannell identifies four phases of the sacralisation of the tourist attraction: the ‘naming phase’, the ‘framing and elevation phases’, the ‘enshrinement phase’, the ‘mechanical reproduction phase’ and finally the social ‘production phases.’ Jules-Rosette and Osborn’s transformational nodes echo MacCannell’s sacralisation phases. Indeed, the influence of MacCannell is notable in the book.

There is no doubt that museums and their contents evoke emotional attachments that include history, politics and other identities and representations. An African visitor to a museum of historic African art can hardly avert the gaze of coloniality, of theft, of home, of ancestry, heritage and a feeling of dislocation. The authors sum up this colonial narrative in three parts: ‘contact and conquest, domination and accumulation and public display’ (39). All three elements were present in the looting of the art works of the Kingdom of Benin.

But the discussion does not confine itself to Western museums but explores also museums in Africa and how Africans regard their artistic creations. African artists are doing great and exciting work, mixing different styles and genres, and the attempt here is to bridge the gap between the Western and African perspectives, to reconcile the primitive and the modern, to make the transition from the colonial to the postcolonial and indeed postmodernist view of African art.

However, much of what the authors have to say about the role of museums in transforming African art could be said about the art of any culture. Remove the discussion on African art and we are left with an interesting museology discourse. The question then is, does this discussion resolve some of the questions that beset African art? This is debatable. The West has historically looked upon African art with certain ambivalence, seeing with one eye a primitive culture, and the other something mysterious, intriguing but no less desirable. The German ethnologist, Frobenius, summed up this Western paradoxical attitude to African art when he famously wrote that ‘I was moved to silent melancholy at the thought that this assembly of degenerate and feeble-minded posterity should be the legitimate guardians of so much loveliness’ (Quoted in Gates, 1990: 25). In sum: how could such beauty emerge from such ugliness? He was referring to the beautiful art objects of Ile Ife of the Yoruba. This view is dated now but the question of loveliness in what sense remains. This curious patronising condescension continues to dog African art, since Africa remains an anthropological paradise, a place the West visits to remind itself of ‘primitive’ cultures. Are these objects lovely because they are primitive, exotic, tribal or are they lovely in an intrinsic sense?

In 2005 Simon Njami, who writes the foreword to this book, helped to curate the 2005 Africa Remix Exhibition. The art critic of The London Evening Standard, Brian Sewell, wrote: ‘my first impression of the exhibition remained after a second and third perambulation that not much of it qualifies as art in any contemporary European sense, and that what little does is so European in its sad inadequacy that it hardly qualifies as African.’ He goes on: ‘this wretched assembly of posttribal artefacts, exhausted materials re-used, and what would pass for the apprentice rubbish of the European art school, has about it the air of a state-run trade fair.’[1] This derogatory putdown is precisely the kind that this book attempts to demolish, suggesting otherwise that African art has moved from the ‘curiosity cabinet’ into the open space of intrinsic value in its own right. To look therefore upon African art through the prism of ‘contemporary European’ eye, merely reprises an out-dated neo-colonial view.

In any case, although the book talks about how African art is being transformed or reframed, but perhaps in the end, it is not museumgoers or society that is transforming African art, it is African art that is transforming society. Art objects do not change; it is people that change and they change in respect of their approaches, perceptions and attitudes upon the fact that each subsequent viewing reveals something previously unnoticed. Gombrich points out in Art and Illusion (1986) that ‘the whole history of art is not the story in technical proficiency, but a story of the changing ideas and requirements’ (22). So-called ‘primitive’ art is not undeveloped art but art that is finished, while the evaluation process rumbles on unconsciously in a re-evaluation of our perceptive apparatuses in much the same way we change spectacles to correct defective eyesight. This is a re-evaluation of ourselves through art. This is what reframing means, a kind of aesthetic turn.

So who owns these works of art? Who legitimizes and appraises their artistic merits and value? The answer sadly is the West. The objects are largely housed in Western museums, viewed largely by Western audiences and discussed in Western media. Western society through its art critics and art lovers determine their aesthetic merits and value, and as to who owns them, again the answer is sadly the West. This is the monopolisation of ownership and appropriation of the arts of other cultures that Clifford (1988) talks about, where the West collects and displays these objects creating a dislocation that turns them into unanchored ‘floating’ pieces in museum spaces. This is art not merely displayed but displaced from its origins that renders it a form of cultural appropriation. With regards to the Benin artworks, what is less appreciated is that until they were stolen these objects were housed in the King’s palace, a museum of a kind and also that pre-colonial African artists did not just fumble their way through creating these artworks; they knew what they were doing and appreciated the aesthetics of their handiwork and so did not require authentication or legitimacy from outsiders. Sadly, as African art increases in market value - they command the highest prices in the West, beyond the affordability of the average African buyer – and sadder still Africans themselves do not get to see them for reasons of little or limited access, which is all part of the Problematizing Global Knowledge (2006, edited by Featherstone, Venn, Bishop et al.) where the sociology of knowledge and the value of African art is centralised in the West. This book does not shy away from these controversies and its thorny contentious, negotiating the terrain with deftness and skill. The questions are: without the museum, where would art of any kind be, but without artists would there be art museums at all? Perhaps a lasting impression is this: art is a collective collaborative process that together produces that thing we call beauty. That process is largely subterranean in the sense that much of that work goes unseen and unnoticed. This book excavates that process and lays it bare, from the artist and his or her work through the museum and finally the consumer. The discussion polishes African art and brings it into greater prominence, as objects of beauty in their own right. To this end this intelligent and thoughtful book makes invaluable contribution to the discourse on African art and museums. This is African art reframed for these times.

[1] “Out of Africa” Brian Sewell The London Evening Standard. Friday 18 February 2005.

References

Becker, Howard (2008) Artworlds. Los Angeles: University of California Press

Bourdieu, Pierre (1993) The Field of Cultural Production: Essays on Art and Literature. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Clifford, James (1988) “On Collecting Art and Culture.” In The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature, and Art, pp.215-251. Cambridge Massachsetts.

Featherstone, Mike; Venn, Couse (eds.) (2006) Problematizing Global Knowledge. London: Sage

Gates, Louis “Canon Formation, Literary History and the Afro-American Tradition: From the Seen to the Told.” In Afro-American Literary Study in the 1990s (1990) 14-38. Edited by Baker, Houston., Redmond, Patricia. Chicago Illinois: University of Chicago.

Gombrich, Ernst (1986[1959]) Art and Illusion. London: Phaidon.

Hume, David (1757[2018]) Of The Standard of Taste. Scotts Valley, California: Createspace Publishing.

MacCannell, Dean (1999[1976]) The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class. LA. California University Press.

Wolff, Janet (1983) Aesthetics and The Sociology of Art. London: Palgrave Macmillan

Wolff, Janet (1984) The Social Production of Art. New York: New York University Press.

Zolberg, Vera L. (1990) Constructing a Sociology of Arts. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Dr. Gabriel O. Apata is an independent scholar and researcher whose works cut across the humanities and social sciences. His research interests include Race, aesthetics, religion, African philosophy, history, politics and diaspora studies.