Earwitnesses of a Coup Night: The Many Media Infrastructures of Social Action

Jussi Parikka

Winchester School of Art

The particularly cruel scenes in Ankara and Istanbul from July 15th and 16th circulated quickly. From eye witness accounts to images detached from their context, media users, viewers and readers was soon seeing the graphic depictions of what had happened with the added gory details, some of them fake, some of them not.

Still and moving images from the hundreds of streams that conveyed a live account of the events left many in Turkey puzzled as to what is going on. Only later most were able to form some sort of a picture of the events with the coherence of a narrative structure. By the morning the live stream on television showed military uniform soldiers raising their hands and climbing down from their tanks. What soon ensued were the by already now iconic images of public punishment: the man with his upper torso bare and the belt as his whip, the stripped soldiers in rows shamed and followed up by the series of images of expressions of collective joy as most of Turkey was relieved again. The coup was over. The unity in resisting the coup was unique. As it was summarised by many commentators: even the ones critical of the governing AK Party’s politics agreed that this was not a suitable manner of overthrowing an elected government.

Image: Twitter screenshot. Source: Joe Parkinson/Twitter.

However, what became evident immediately in the wake of the actual events was the quick spread of narratives and explanations about the coup night and its extent. As one journalist aptly and with a healthy dose of sarcasm put it:

The flux of commentaries on social media and in newspapers, columns and television deserved its own name: “coupsplaining” as @shokufeyesib coined it.

Also some rather established organisations like Wikileaks got quickly on the spectacle-seeking bandwagon of the coup attempt’s repercussions. Turkish journalists and activist soon read and revealed that the so-called “AKPleaks”-documents were not really anything that interesting as it was advertised to be. As Zeynep Tufekci summarised: “According to the collective searching capacity of long-term activists and journalists in Turkey, none of the ‘Erdogan emails’ appear to be emails actually from Erdogan or his inner circle” while actually containing information that could be considered harmful to normal Turkish citizens instead.

Of course, besides commentators inside and outside Turkey, there was no lack of people with first-hand experience. Besides the usual questions that eyewitnesses were asked in many news reports about “how did things look like”, another angle was as pertinent. How did it sound? The soundscape of the coup was itself a spectacle catered to many senses: the helicopters hovering around the city; the different calibre gunfire that ranged from heavy fire from helicopters to individual pistol shots; individual explosions; car horns; sirens, and the roaring F-16 that descended at times so low so that its sonic boom broke windows of flats. Such sonic booms have their own grim history as part of the 21st century sonic warfare as cultural theorist Steve Goodman analysed the relation of modern technologies, war and aesthetics. As has been reported for years, for example, Israeli military has used sonic noise of military jets in Palestine as a shock technique: “Palestinians liken the sound to an earthquake or huge bomb. They describe the effect as being hit by a wall of air that is painful on the ears, sometimes causing nosebleeds and 'leaving you shaking inside'."

In the midst of sonic booms, a different layer of sound was felt through the city: the mosques starting their extraordinary call to prayer and calls to gather on the streets. The latter aspect was itself triggered by multiple mediations that contributed to the mobilization of the masses. Turkish President had managed to Facetime with CNN-Turk’s live broadcast and to call his supporters to go on the streets to oppose the coup attempt. By now even the phone the commentator held has become a celebrity object with apparently even $250,000 offered for it.

But there was more to the call than the ringtone of an individual smartphone. In other words, the chain of media triggers ranged from the corporate digital videotelephony to television broadcasting to the infrastructures of the mosques to people on the streets tweeting, filming, messaging and posting on social media. All of this formed a sort of a feedback-looped sphere of information and speculation, of action and messaging, of rumours and witnessing. Hence, there was more than just traditional broadcast or digital communication that made up the media reality of this particular event.

The mosques started to amplify the political leadership’s social media call by their own acoustic means. Another network than just social media was as essential and it also proved to be irreducible to what some called the “cyberweapon” of online communications. As one commentator tried to argue commenting on the events in Turkey: “But, this is the era of cyberpower. Simply taking over the TV stations is not enough. The Internet is a more powerful means of communication than TV, and it is more resilient — especially with a sophisticated population.” However, there were also other elements in the mix that made it a more interesting and a more complex issue than merely about the “cyber”.

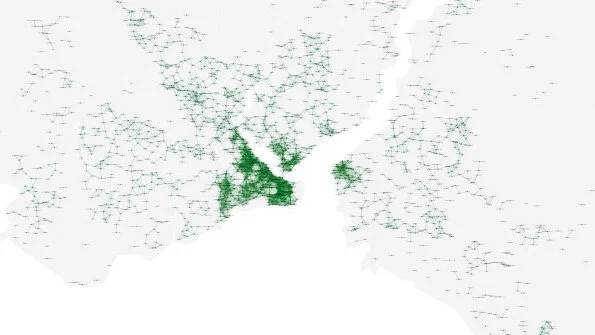

Image: ‘Islam, Republic, Neoliberalism’ network maps. Source: Burak Arikan.

Turkish artist and technologist Burak Arikan had already in his earlier work mapped the urban infrastructure of Istanbul in terms of its mosques, malls and national monuments. “Islam, Republic, Neoliberalism” (2012) employs his critical mapping methodology to visualise how structures of power are part of the everyday whether we always realise these relationships or not. Based on his research, Arikan devised three maps of those architectural forms and how they connect. According to Arikan, the “maps present a comparative display of network patterns that are formed through associations linking those architectural structures that represent the three dominant ideologies –Islam, Republic, Neoliberalism– in Turkey.”

During the coup weekend, it was the network of the mosques and their minarets that became suddenly very visible – or actually, very audible. While the regular praying times have become such an aural infrastructure of the city that one does not necessarily consciously notice it, the extraordinary calls from imams reminded how dense this social, architectural fabric actually is. The thousands of Istanbul mosques became itself an explicit “sonic social network” where the average estimated reach (300 meters) of sound from the minarets is too important of a detail to neglect when one wants to understand architecture as solidifying social networks in contemporary Turkey. In the context of mid-July it was one crucial relay of communication between the private sphere in homes, the streets and the online platforms contributing to the mobilization of the masses. The musicological perspective has highlighted how sound and noise negotiate conflict across private and the public and we can extend this to a wider media ecological perspective too. This is where art and design practices can have an instrumental role to play in helping us to understand such overlapped media and sensorial realities.

Image: ‘Islam, Republic, Neoliberalism’ network maps. Source: Burak Arikan.

Artists such as Arikan have investigated the ways how online tools and digital forms of mapping can connect to issues of urban planning and change. The visual artwork helps us to also understand how there are other social realities, less front of our eyes even if they are in our ears. This expands the wider sense of how media is and was involved in Turkey’s events, and it gives also insights to new methodologies of artistic intervention in understanding the coupling of media, architecture, visual methods and the sonic reality of urban life. And in this case of the bloody events of the coup weekend, much of the personal experience of “what happened” is now being narrated in Turkey in terms of what it sounded like – another aspect of the media reality of the coup attempt’s aftermath.

This article was originally published at: https://jussiparikka.net/2016/08/04/ear-witnesses-of-a-coup-night/