Simone M. Hüning: Criminalizing Poverty and Fragmenting the City in Brazil

Simone M. Hüning

Abstract

Image: Simone M. Hüning.

This article discusses practices of hygienism and social cleansing in Brazilian urban spaces. It takes the case of a traditional fishing community located in north-eastern Brazil that is under the threat of being evicted from the area occupied for more then 60 years, while locals are accused of holding dangerous and violent ways of life. These practices are considered, from a Foucauldian perspective, as part of biopolitcal strategies connected with state racism, that in contemporary society underpin a discourse of social security and development. It also discusses how the criminalization of certain social groups is used to justify, on the one hand, the restriction to certain spaces, and, on the other, privileged forms of access to public space.

Image: Boats in the Community. Source: Photo Blog AMAJAR.

Hosting the World Cup and the Olympic Games brought to the Brazilian public agenda the forced displacement of residents from urban areas for building the infrastructure for these events. However, the violent and massive way these situations occurred, especially before the World Cup, is not restricted to cities that host the events, nor does it constitute a novelty in the ways of governing urban spaces in Brazil.

According to Outtes (2003) physical and moral hygienism constitute the urban planning in Brazil, particularly in large cities, from the late XIX and early XX centuries. An important aspect of this strategy lies on the production of prejudice and fear of certain spaces and social groups, thus creating a justification for interventions such as removals and “social cleansing”. This leads us to reflect on how contemporary biopolitical strategies connect to state racism to govern specific populations (Foucault, 2003). Foucault argues that state racism enables the production, hierarchization and qualification of people in different categories within a population, such as good and bad citizens, the ones that must be protected and the ones from whom the society must be protected. Underpinning a discourse of social security and development, the protection against these categories make justifiable a range of actions performed by the State against marginalized groups, including the forced displacement of people in urban areas.

Looking at Maceió, a seaside town located in north-eastern Brazil and with great potential for tourism, we can see how this form of governing of the cities is present in current days. Maceió brings together some of the worst human development index in Brazil, in areas such as education, unemployment, poverty and violence. Remarkably divided between rich (especially near the sea) and poor areas, the city is distinguished between secure territories (to the cost of private security technologies and companies) and danger zones, associated with poverty. In addition, the extreme social and economic inequality, together with the fear of crime, amplify the production of more segregation and exclusion of groups considered undesirable from the most visible areas of the city.

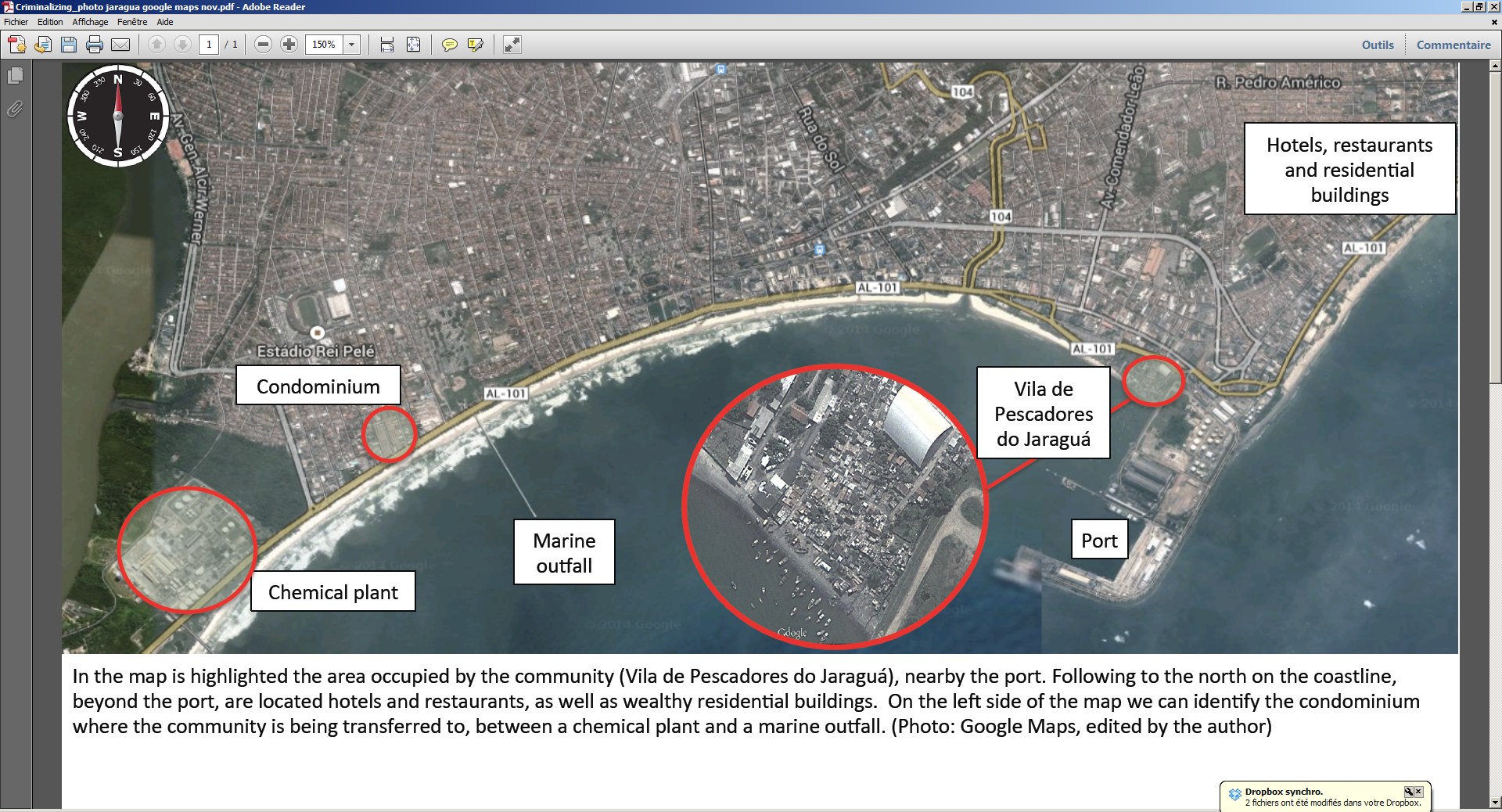

Image: Vila de Pescadores do Jaraguá. Source: Google Maps, edited by author.

This kind of social segregation is currently experienced by a traditional fishing community, Vila de Pescadores do Jaraguá, which has lived for more than 60 years in a historic district of Maceió, in an area that belongs to the Brazilian Union and is located very close to the noblest and most expensive regions of the city. Often called “favela” (slum), the community was neglected by the government in the last decade, suffering a lack of investment in public policies and services. Now, blamed for the precariousness that resulted from the lack of investment, the community is under the threat of being completely evicted from the area by the municipal government, so that the area can be used to build projects to embellish the city and meet the demand of tourism development. The conflict is registered in the “Mapa de conflitos envolvendo injustiça ambiental e saúde no Brasil” (Map of conflicts involving environmental injustice and health in Brazil), produced by the renowned Brazilian research institute Fiocruz (2010), and one of the risks highlighted on this map is the change in the traditional regime of use and occupation of the territory, which will surely be exacerbated by the removal of the community from this area.

Image: Dweller’s meeting to discuss resistance strategies. Source: Ávila Menezes.

The eminence of a forced removal of the residents who resist the previous removal actions of the municipality, shows a clear case of violation of the right to housing and the power of discourses of fear, danger and criminalization of poor communities to justify and legitimize the need of removing these people from the place where they currently live. A narrative was built around the community featuring locals and their way of life as dangerous and violent, therefore public enemies, considering the permanence of these people in this space as an impediment to urban development of the region.

City Hall offered the people who work on the fishing, apartments in a condominium built approximately 3km from the village, near a chemical plant, where accidents such as spills of toxic substances are frequent and therefore an area with no value on the property market (Albuquerque, Peixoto & Albuquerque, 2012). More than half of the community has been moved to this condominium, leaving remaining in the original location a group of families who in addition to working directly with fishing have strong bonds of affection with this place. It is not difficult to conclude that the removal of a community to a peripheral area would not contribute to any aspect of crime reduction, if this was indeed a problem, which is denied by the representative of the military police who said there was no discrepancy between the crime rates on the Vila de Pescadores and other related areas.

Image: Dweller’s protest in front of the community. Source: Ana Luiza Azevedo Firemann.

Thus, the situation experienced by the community converges to the analysis developed by Caldeira (1996), regarding the production of stereotypes about certain social groups named as dangerous, producing rigid boundaries and segregation in cities and increasing inequality and social distances. Besides involving a series of rights violations, disqualifying people and reiterating prejudice, such positions, assumed by the municipal government on this conflict, reaffirm a policy of urbanization based in the fragmentation of spaces and social groups. In the city with the highest murder rate in Brazil and strong appeal to tourism, it is essential to reflect on how these indexes relate to the way public spaces are used and designed, and how projects based on arguments to combat crime, beautify the city and boost tourism spaces, are segregating and excluding local people in their areas.

The current proposal of the municipality, after full disclosure of a project to build a marina on the area (now denied) where the current fishing community resides, is to build what they call a "modern public facility". There is expected to be a support centre for fishing activity – after the expulsion of the fishing community (!) –, and a huge parking lot in front of another parking area already idle, whose space alone, already entails the construction of houses for families who remain in the community. But it seems that in our modern cities, cars matter more than people. Such a project is imposed by the municipal administration despite the existence of a doable project, dated of 1997, which envisaged revitalization of the Vila de Pescadores, housing construction, thus ensuring the respect for people and the cultural heritage of the place.

Furthermore, although there are legal dispositions at local (Lei Orgânica do Município de Maceió, 2003), federal (Medida Provisória n. 2.220/2001, Estatuto da Cidade (Statute of the City)) and international levels (Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, 1989 No. 169) that would ensure the right to this population to remain in the territory, the unfolding of this process, along with other cases of removal of the poor people in Brazil, point us to the prevalence of economic interest at the expense of the human aspect in the planning of cities. The criminalization of poverty and the production of disposable and undesirable lives prevail in the contemporary urban landscape that must be embellished to the development of tourism. This legitimizes, another hygienist process in the governing of the city, while the criminalization of certain social groups is used to justify, on the one hand, the restriction to certain spaces, and, on the other, privileged forms of access to public space. The urbanization process in Brazil was and continues to be based on a fragmentary, hygienic and eugenic approach.

References

Albuquerque AA, Peixoto, GV and Albuquerque AMG (2012) Uma demonstração do vigor da cidade: a resistência dos pescadores do Jaraguá, Maceió-Al. Anais do III Seminário Internacional Urbicentros. Outubro 1-20.

Caldeira TPR (1996) Fortified enclaves: the new urban segregation. Public Culture. 8(2): 303-328.

Fiocruz (2010). Mapa de conflitos envolvendo injustiça ambiental e saúde no Brasil. Available at: http://www.conflitoambiental.icict.fiocruz.br/index.php?pag=ficha&cod=331 (accessed 10 July 2014).

Foucault M (2003) Society must be defended. London: Penguin Books.

Hüning S M (forthcoming) Encontros e confrontos entre a vida e o direito. Revista Psicologia em Estudo.

Outtes J (2003) Disciplining Society through the City: The Genesis of City Planning in Brazil and Argentina (1894-1945). Bulletin of Latin American Research 22(2): 137-164.

Related Material:

Theory, Culture & Society special section on ‘Latin America’, edited and introduced by José Maurício Domingues, Volume 26 Issue 7-8, December 2009.

Theory, Culture & Society special section on ‘The Urban Problematic’, edited and introduced by Ryan Bishop and John WP Phillips, Volume 30 Issue 7-8, December 2013.

On the TCS Website:

Book Review: Angelo Martins Junior on ‘Periphery’ and Brazil: http://theoryculturesociety.org/book-review-angelo-martins-junior-on-periphery-and-brazil/

Simone Maria Hüning has a PhD in Psychology and is a professor at Universidade Federal de Alagoas (UFAL), Brazil, where coordinates a research group on Cultural Processes, Policies and Modes of Subjectivation. She co-edited the book Foucault e a Psicologia (EDIPUCRS, 2009) and published papers on Social Psychology and Foucauldian studies. At moment she is an academic visitor at the King’s Brazil Institute, Kings College London where is developing her post-doctoral research sponsored by CAPES (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior).

Email: simonehuning@yahoo.com.br